I might not have the stomach for full on horror (and have been scared out of a nights sleep by Stephen King) but when the nights have either drawn out (there's something deeply unsettling about the hours of half light that constitute a midsummers night in the North) or drawn in something a little bit spooky is fun.

I have a fairly extensive collection of vintage horror stories - or maybe gothic tales is a better catch all title for their general mood - to attest to that belief, and quite a pile to go through at the moment.

I'm currently reading my way through the British Library's collection of werewolf stories, 'Silver Bullets', selected by Emma Dobson. It's excellent, and rather like last years 'Lost in a a Pyramid' (mummies) it has a few surprises. Nothing in it has been especially scary yet (I'm 3/4 of the way through) so it's a perfectly acceptable book to retire to bed with.

It was 'Lost in a Pyramid' that introduced me to Arthur Conon Doyle in gothic mode, and in turn made the OUP's handsome edition of his collected 'Gothic Tales' very timely. It's an excellent rainy day book, especially when it's just getting dark outside.

There's a 'Collected Ghost Stories' of M. R. James in the same series (I love these cloth covers) and whilst I've read some of the obvious ones in other anthologies I really don't know James well enough. What I have read has more than persuaded me that he's just the sort of writer that I like though, so I'm looking forward to becoming better acquainted with him.

I bought Henry Chapman Mercer's 'November Night Tales' on the back of a comparison to M R James - and the general description of him as an eccentric archaeologist, historian, architect, and collector with a love of gothic literature (he sounds great). This edition is published by Valancourt Books and might feature a Transylvanian werewolf - I didn't particularly mean to save it for November, but now November is all but here it's going to the top of the tbr pile.

I've also been dipping in and out of 'Dracula's Brethren', it's edited by Richard Dalby and Brian J. Frost. I've got a few anthologies edited by Dalby, and all of them are excellent. So far 'Dracula's Bretheren' is no exception. These are vampire tales from between 1820 and 1910, both inspiring and inspired by Bram Stoker's 'Dracula'.

It might be that my first drink of choice to go with any of these books would be a reassuring hot chocolate, but as it's Halloween tomorrow it seemed like a good time to try mix up a version of a 'Corpse Reviver'. Possibly because it's such a great name for a cocktail the Corpse Reviver has had several incarnations (it's also a testament to the popularity of the hair of the dog theory - which is a rubbish theory, but is now making me think of werewolves, so that's something), the one I would have liked to try is the N° 1 which calls for 1/4 Italian vermouth, 1/4 calvados, and 1/2 brandy, but I have neither the calvados or the Italian vermouth in the house so it'll have to wait.

The Corpse Reviver N°2 (from the Savoy cocktail book) is Gin based, it specifies Kina Lillet for the vermouth, which is no longer made, but the internet seems happy with a non specific French dry vermouth instead. As liberties have already been taken with the original recipe dropping the dash of absinthe, unavailable for years anyway as well as being a spirit I loathe, doesn't feel to iconoclastic. If you have a Pastis to hand that would be the obvious substitute, I have Kümmel which is more caraway than anise, but at least I like it.

This Corpse Reviver is equal measures of lemon juice, dry vermouth, Cointreau, and gin, with a dash of absinthe/pastis/kümmel all shaken well over ice and strained into a cocktail glass. The kümmel, considering it was only a dash, really makes its presence felt, the vermouth not as much as I expected. There's a strong family resemblance to a Silver Bullet (gin, lemon juice, kümmel) a pleasing balance between sweet and sour, and it's not quite as strong as the name might suggest. Taken in moderation it's also proved effective for reviving me after a tiresome day at work.

Monday, October 30, 2017

Sunday, October 29, 2017

Country Matters - Clare Leighton

The day the clocks go back is reliably my favourite day of the year; that hour feels like such a gift, and today has been reasonably productive. I've made Quince and star anise jelly from Diana Henry's brilliant 'Salt, Sugar, Smoke' (it's such a good book for all sorts of preserving). I love this jelly, and am surprised that I don't seem to have written about it before here. It's excellent with all sorts of meats, cheese, and atva oush good on a scone too. I've made it every year since I found the recipe (2012?) and would hate to be without a jar now.

I've also got my first Christmas cake in the oven, have spent time with family and friends, hoovered, been to see a film, bought Christmas cards, and discovered a stain on the airing cupboard ceiling which I hope isn't an indication of yet another bloody leak (it could be the marks from a previous leak coming back through the paint. Fingers crossed) and met my new upstairs neighbour. All in all a full day. It's amazing the difference an extra hour makes.

I like the dark nights too, this is the time of year when living in a city comes into its own. Leicester is caught between the lights of Diwali and Christmas, it's a cheerful place to be at the moment with piles of fallen leaves to kick through, but no gaunt hedgerows for the wind to whistle around. There's none of the eeriness of the autumnal countryside.

It still surprises me how much easier I find it to be in tune with the seasons in a town rather than the country, but it's here that I can walk everywhere seeing the year turn whilst I do so, and here too that shops and market stalls are full of the seasonal produce that just as clearly Mark the approach of winter as those falling leaves.

I don't know what Clare Leighton would make of today's villages. Some things perhaps haven't changed so very much, but the world she writes about and engraves here was already disappearing in the 1930's when she recorded it. Reading this book I recognise glimpses of what she describes, but rather in the way you can trace a family likeness between grandparents and grandchildren. There are still flower and produce shows, still pubs with locals who have their particular spots, still village cricket, but the chair bodgers, tramps, smithy's - they're all gone. So too has the village witch, and I think it's illegal to pick wild flowers now, so no more primrose gathering.

It was the engravings that attracted me to this book, I've always liked Leighton's woodcuts - her writing turns out to have the same bold clarity to it, and the same lack of sentimentality in its observations. There is plenty of affection for the community and way of life that she's making her subject, and she must have known some of these figures were anomalies even as she wrote about them but I don't feel that nostalgia is the driving force here, though it easily could have been. Rather it's a reminder to look at what's around, and to appreciate the rhythm of a life dictated by the seasons.

It's a beautiful book (from Little Toller Books who find and produce wonderful things) that feels just right for a day balanced between autumn and winter.

I've also got my first Christmas cake in the oven, have spent time with family and friends, hoovered, been to see a film, bought Christmas cards, and discovered a stain on the airing cupboard ceiling which I hope isn't an indication of yet another bloody leak (it could be the marks from a previous leak coming back through the paint. Fingers crossed) and met my new upstairs neighbour. All in all a full day. It's amazing the difference an extra hour makes.

I like the dark nights too, this is the time of year when living in a city comes into its own. Leicester is caught between the lights of Diwali and Christmas, it's a cheerful place to be at the moment with piles of fallen leaves to kick through, but no gaunt hedgerows for the wind to whistle around. There's none of the eeriness of the autumnal countryside.

It still surprises me how much easier I find it to be in tune with the seasons in a town rather than the country, but it's here that I can walk everywhere seeing the year turn whilst I do so, and here too that shops and market stalls are full of the seasonal produce that just as clearly Mark the approach of winter as those falling leaves.

I don't know what Clare Leighton would make of today's villages. Some things perhaps haven't changed so very much, but the world she writes about and engraves here was already disappearing in the 1930's when she recorded it. Reading this book I recognise glimpses of what she describes, but rather in the way you can trace a family likeness between grandparents and grandchildren. There are still flower and produce shows, still pubs with locals who have their particular spots, still village cricket, but the chair bodgers, tramps, smithy's - they're all gone. So too has the village witch, and I think it's illegal to pick wild flowers now, so no more primrose gathering.

It was the engravings that attracted me to this book, I've always liked Leighton's woodcuts - her writing turns out to have the same bold clarity to it, and the same lack of sentimentality in its observations. There is plenty of affection for the community and way of life that she's making her subject, and she must have known some of these figures were anomalies even as she wrote about them but I don't feel that nostalgia is the driving force here, though it easily could have been. Rather it's a reminder to look at what's around, and to appreciate the rhythm of a life dictated by the seasons.

It's a beautiful book (from Little Toller Books who find and produce wonderful things) that feels just right for a day balanced between autumn and winter.

Saturday, October 28, 2017

A Game of Chess and Other stories - Stefan Zweig

I'd dearly love to be able to take a month off work to enjoy autumn as it turns into winter, read a pile of the books that have already waited too long for some attention, and bake. It's not on the cards. Zweig is the kind of writer that really makes me wish it was otherwise though. It's not so much that I get so absorbed in his stories that I struggle to put them down, although there's an element of that, it's the threads of thought he unravels and I desperately want to follow through other books, but don't have the time to.

This collection is published by Alma Classics and includes 'The Invisible Collection' (brilliant), the novella length 'Twenty Four Hours in a Woman's Life', which explores infatuation and addiction, 'Incident on Lake Geneva' which specifically addresses the pointlessness of war, and 'A Game of Chess', Zweig's last story - written whilst in exile in Brazil.

'Twenty Four Hours in a Woman's Life' is set pre World War One. In a hotel on the Riviera a group of guests fall into argument over an unfolding scandal; a previously respectable married woman has run off with a young man she's had but a couple of conversations with. Partly to play devils advocate our narrator defends her, which leads a fellow guest to confide a story from her past to him.

As a middle aged widow she tried to help a young gambler, the situation quickly spirals out of her control, and she finds herself behaving in ways she scarcely understands, and which will characterise how she sees herself - at least until this confession. It's got Zweig's trademark pathos and compassion running all through it.

'A Game of Chess' by comparison is full of anger barely contained by Zweig's elegance of style, there is nothing to soften the story as it unfolds (as there is in The Invisible Collection) just a stark portrayal of how effectively cruel fascism is.

Altogether this is an excellent place to start if your unfamiliar with Zweig - the stories are a good cross section (I'm saying that with all the authority of someone who has read one novel and 4 other stories before this) and it's a very reasonably priced edition (rrp £4.99), and a nicely judged collection if you don't already have the stories elsewhere. The more I read Zweig, the more I like him.

This collection is published by Alma Classics and includes 'The Invisible Collection' (brilliant), the novella length 'Twenty Four Hours in a Woman's Life', which explores infatuation and addiction, 'Incident on Lake Geneva' which specifically addresses the pointlessness of war, and 'A Game of Chess', Zweig's last story - written whilst in exile in Brazil.

'Twenty Four Hours in a Woman's Life' is set pre World War One. In a hotel on the Riviera a group of guests fall into argument over an unfolding scandal; a previously respectable married woman has run off with a young man she's had but a couple of conversations with. Partly to play devils advocate our narrator defends her, which leads a fellow guest to confide a story from her past to him.

As a middle aged widow she tried to help a young gambler, the situation quickly spirals out of her control, and she finds herself behaving in ways she scarcely understands, and which will characterise how she sees herself - at least until this confession. It's got Zweig's trademark pathos and compassion running all through it.

'A Game of Chess' by comparison is full of anger barely contained by Zweig's elegance of style, there is nothing to soften the story as it unfolds (as there is in The Invisible Collection) just a stark portrayal of how effectively cruel fascism is.

Altogether this is an excellent place to start if your unfamiliar with Zweig - the stories are a good cross section (I'm saying that with all the authority of someone who has read one novel and 4 other stories before this) and it's a very reasonably priced edition (rrp £4.99), and a nicely judged collection if you don't already have the stories elsewhere. The more I read Zweig, the more I like him.

Thursday, October 26, 2017

Leighton House Museum for Alma-Tadema

We've been meaning to go to Leighton house for years, but it's just far enough out of the way (Holland Park) for there to never be quite enough time to get there when we're in London. D particularly wanted to see the Alma - Tadema At Home in Antiquity exhibition though (has a soft spot for him), and as this is its final week we made the effort.

The exhibition was excellent, I'm not quite the fan that D is; the classical settings that Alma-Tadema is best known for don't particularly excite me, but the chance to evaluate him as an artist did. Something that was really fascinating was seeing how a technically very accomplished artist could still make a real hash of some things - there are figures in some of the paintings which just don't look right. In life and as a group it's also really striking how respectably Victorian his classical ladies look.

The big discovery was that Alma-Tadema's wife and daughters were accomplished painters, and are well represented here. There's something really encouraging about that - they're all part of the same story, he clearly fostered their talents, and the overall impression is of a wonderfully creative and colourful household.

Anothet thing I hadn't really understood is how much Alma - Tadema's vision of the classical world has informed filmmakers either - understandable in the early days (there are clips from films, some of which are roughly contemporary with his life, or from within a couple of years of his death) but somehow surprising when you see how Ridley Scott clearly references him for 'Gladiator'.

Meanwhile Leighton house is amazing. Unfortunately they don't allow photos (which I respect when it comes to other people's pictures, but find frustrating when it applies to architectural details). Built for Leighton and continuously added to throughout his life, it became a museum not long after he died, but had suffered somewhat over the years. A major refurbishment in the last decade has done its best to restore the original decorative scheme. Do a quick search for images, you won't be disappointed.

Leighton, who never married, only ever had one bedroom built (excluding servants quarters in the basement), so the house is mostly spaces for public entertaining, or for working in, with the stars of the show being the Arab hall, and the narcissus hall. Opulent is the word for these. The Arab hall with its gilding, beautiful tiles, fret worked shutters, stained glass, pool, and cushioned recesses for lounging is straight out of the Arabian nights. The glorious blue of the Narcissus hall has tiles the same shade of blue as a stuffed peacock that sits on a pedestal half way up the stairs - next to a sort of built in sofa with the fattest cushions I've ever seen (not only no photos, no sitting either). It's all utterly magnificent - and now we know where it is we'll go back.

The exhibition was excellent, I'm not quite the fan that D is; the classical settings that Alma-Tadema is best known for don't particularly excite me, but the chance to evaluate him as an artist did. Something that was really fascinating was seeing how a technically very accomplished artist could still make a real hash of some things - there are figures in some of the paintings which just don't look right. In life and as a group it's also really striking how respectably Victorian his classical ladies look.

The big discovery was that Alma-Tadema's wife and daughters were accomplished painters, and are well represented here. There's something really encouraging about that - they're all part of the same story, he clearly fostered their talents, and the overall impression is of a wonderfully creative and colourful household.

Anothet thing I hadn't really understood is how much Alma - Tadema's vision of the classical world has informed filmmakers either - understandable in the early days (there are clips from films, some of which are roughly contemporary with his life, or from within a couple of years of his death) but somehow surprising when you see how Ridley Scott clearly references him for 'Gladiator'.

Meanwhile Leighton house is amazing. Unfortunately they don't allow photos (which I respect when it comes to other people's pictures, but find frustrating when it applies to architectural details). Built for Leighton and continuously added to throughout his life, it became a museum not long after he died, but had suffered somewhat over the years. A major refurbishment in the last decade has done its best to restore the original decorative scheme. Do a quick search for images, you won't be disappointed.

Leighton, who never married, only ever had one bedroom built (excluding servants quarters in the basement), so the house is mostly spaces for public entertaining, or for working in, with the stars of the show being the Arab hall, and the narcissus hall. Opulent is the word for these. The Arab hall with its gilding, beautiful tiles, fret worked shutters, stained glass, pool, and cushioned recesses for lounging is straight out of the Arabian nights. The glorious blue of the Narcissus hall has tiles the same shade of blue as a stuffed peacock that sits on a pedestal half way up the stairs - next to a sort of built in sofa with the fattest cushions I've ever seen (not only no photos, no sitting either). It's all utterly magnificent - and now we know where it is we'll go back.

Wednesday, October 25, 2017

How to be a Kosovan Bride - Naomi Hamill

'How to be a Kosovan Bride' is Hamill's debut novel, in it she follows the lives of two teenage girls from the same village; the Kosovan Bride of the title who marries into a family as traditionally minded as her own, and the Returned Girl, sent back to her family on her wedding night when her new husband suspects she isn't a virgin.

The Kosovan Bride moves into a house with her in laws, soon finds herself pregnant, and with a future fully mapped out for her. The Returned girl is in relatively unchartered territory and seizes the opportunities that her new set of choices bring her.

Hamill's knowledge of Kosovo comes from the visits she's made there working with a U.K charity, the lingering legacy of the war, and the persecution of ethnic Albanians threads through the book both in the form of the early memories of the girls, and the stories they manage to get their families to share. This is all the more powerful for focusing on the everyday reality of life for very ordinary people in extraordinarily difficult circumstances - it's a stark portrayal of the reality of life as a fugitive or refugee.

For the Kosovan Bride the difficulty is in reconciling the hopes and expectations of a contemporary girl, familiar with social media, and images of a world far beyond her village, with the reality of a very traditional marriage and equally rigid expectations. It's a society that sets a very high value on honour and where blood feuds and a general threat of violence are not just a possibility, but a very real threat. Hamill makes it easy to understand why that tradition is so important to the generation that made it through the conflicts of the late 1990's, and to their children as well. She also makes it clear that that tradition is quite a burden for bright young women to accommodate.

For the Returned girl there's the chance to turn her back on some of those traditions, she finishes School, goes to university, plans a different life for herself, meets men on her own terms, starts to write the stories she hears of the past, and finds her own ways to reconcile what she wants with respect for her family's traditions.

The book has the rhythm of a set of fairy tales, and actually also incorporates a traditional fairy tale within it. It's sparse, and effectivley repetitive delivery is both utterly compelling and powerful. It also made me realise that despite knowing some Albanian refugees back around 2000, I know woefully little about this part of recent history. Altogether a remarkable book.

The Kosovan Bride moves into a house with her in laws, soon finds herself pregnant, and with a future fully mapped out for her. The Returned girl is in relatively unchartered territory and seizes the opportunities that her new set of choices bring her.

Hamill's knowledge of Kosovo comes from the visits she's made there working with a U.K charity, the lingering legacy of the war, and the persecution of ethnic Albanians threads through the book both in the form of the early memories of the girls, and the stories they manage to get their families to share. This is all the more powerful for focusing on the everyday reality of life for very ordinary people in extraordinarily difficult circumstances - it's a stark portrayal of the reality of life as a fugitive or refugee.

For the Kosovan Bride the difficulty is in reconciling the hopes and expectations of a contemporary girl, familiar with social media, and images of a world far beyond her village, with the reality of a very traditional marriage and equally rigid expectations. It's a society that sets a very high value on honour and where blood feuds and a general threat of violence are not just a possibility, but a very real threat. Hamill makes it easy to understand why that tradition is so important to the generation that made it through the conflicts of the late 1990's, and to their children as well. She also makes it clear that that tradition is quite a burden for bright young women to accommodate.

For the Returned girl there's the chance to turn her back on some of those traditions, she finishes School, goes to university, plans a different life for herself, meets men on her own terms, starts to write the stories she hears of the past, and finds her own ways to reconcile what she wants with respect for her family's traditions.

The book has the rhythm of a set of fairy tales, and actually also incorporates a traditional fairy tale within it. It's sparse, and effectivley repetitive delivery is both utterly compelling and powerful. It also made me realise that despite knowing some Albanian refugees back around 2000, I know woefully little about this part of recent history. Altogether a remarkable book.

Sunday, October 22, 2017

Sunday and some Books to look forward to in 2018

It's been a busy old week work wise, partly because our buyers threw us a big tasting session on Friday. This involves a trip to London and as it's a day out of the shop it has a real holiday feel to it, it's also a chance to bitch with colleagues about all the things that frustrate us (currently this mostly seems to be a lack of Chablis), and try some excellent wines. The last is important, it might sound like pure self indulgence to spend an afternoon getting re-acquainted with Krug, Taittinger Comte de Champagne, Veuve's Grande Dame, and Pol Roger's Cuvée Winston Churchill (my personal favourite against some stiff competition, I could have reported on the current vintage age of Dom Perignon too, but some rotter finished it before I got a look in) but you have to spit, and this is the stuff that customers want to know is worth the money. Somebody has to do the research.

It would have been even more fun (it's the highlight of my working year) if I hadn't been coming down with a cold - a blocked nose makes tasting very hard, but I did my best. Happily I got to recuperate whilst dog sitting for my mother. It was a perfect combination of fresh air whilst I was walking her, and napping on the sofa when I wasn't, and now I'm back home with the Oxford University Press trade catalogue for the first half of 2018, and a cup of the best hot chocolate I've ever had the pleasure of meeting. It's Kate Young's Chocolatl recipe (inspired by Philip Pullman's Northen Lights) and is the perfect combination of thick creamy chocolate, aromatic spice, salt, and a couple of things you'll need to check the book for. It's just wonderful.

Also wonderful is the OUP trade list. It's a toss up between this and the British Library list as to which is my favourite (both have a particularly high ratio of the kind of books I get particularly excited about). So wonderful I'm here to share my personal highlights.

I'm intrigued by 'Prohibition a concise history', by W. J. Rorabaugh. I'm interested in the cultural history of alcohol generally, the idea of the Prohibition era is evocative, but I really don't know enough about it.

Patricia Fara's 'A Lab of One's Own' is being published to help mark the centenary of women gaining the vote in this country, and it sounds timely. It looks at the women who stepped into the labs during the First World War, women who carried out pioneering research, and were then unceremoniously pushed back out of the lab again when the men returned. Stories like this need to be told, both to inspire, and to challenge the prejudices that still limit women in science.

Jane Stevenson's 'Baroque Between the Wars' promises to take a fresh look on the arts between 1918-1939 and explore how baroque offered a completely different way of being modern. I think this one sounds fascinating.

There are also more of the beautiful cloth bound hardback Oxford editions coming out. These books are gorgeous so I'll be very tempted at the prospect of replacing my tatty old paperback copy of 'The Mabinogion' (which I think I really need to read again), and it will clearly be the year to finally discover the weird fiction of Arthur Machen (The Great God Pan and Other Horror Stories).

It's the bicentenary of Emily Brontë's birth next year too, so there's an updated reissue of 'The Oxford Companion to The Brontë's'. I'm not the biggest Brontë fan, but even so this sounds desirable.

I'm still battling with Zola's 'The Sin of Abbé Mouret' (I will get there, but his take on rural life is both disturbing and heavy going. If ever there was a case of something nasty in the woodshed, and a man prepared to describe it in hysterical detail...) but that's not putting me off a sense of excitement about 'His Excellency Eugène Rougon'. I'm hoping Zola on court and political circles will be as good as Zola in 'Money'.

And finally, the book I'm really excited about. 'The Scarlet Pimpernel' is getting the World's Classics treatment. I have mentioned before how obsessed with this book I was aged about 11. I read it time after time, and whilst my enthusiasm for it has abated somewhat I'm still fond of it, I have never looked forward to reading the introduction of a book more.

It would have been even more fun (it's the highlight of my working year) if I hadn't been coming down with a cold - a blocked nose makes tasting very hard, but I did my best. Happily I got to recuperate whilst dog sitting for my mother. It was a perfect combination of fresh air whilst I was walking her, and napping on the sofa when I wasn't, and now I'm back home with the Oxford University Press trade catalogue for the first half of 2018, and a cup of the best hot chocolate I've ever had the pleasure of meeting. It's Kate Young's Chocolatl recipe (inspired by Philip Pullman's Northen Lights) and is the perfect combination of thick creamy chocolate, aromatic spice, salt, and a couple of things you'll need to check the book for. It's just wonderful.

Also wonderful is the OUP trade list. It's a toss up between this and the British Library list as to which is my favourite (both have a particularly high ratio of the kind of books I get particularly excited about). So wonderful I'm here to share my personal highlights.

I'm intrigued by 'Prohibition a concise history', by W. J. Rorabaugh. I'm interested in the cultural history of alcohol generally, the idea of the Prohibition era is evocative, but I really don't know enough about it.

Patricia Fara's 'A Lab of One's Own' is being published to help mark the centenary of women gaining the vote in this country, and it sounds timely. It looks at the women who stepped into the labs during the First World War, women who carried out pioneering research, and were then unceremoniously pushed back out of the lab again when the men returned. Stories like this need to be told, both to inspire, and to challenge the prejudices that still limit women in science.

Jane Stevenson's 'Baroque Between the Wars' promises to take a fresh look on the arts between 1918-1939 and explore how baroque offered a completely different way of being modern. I think this one sounds fascinating.

There are also more of the beautiful cloth bound hardback Oxford editions coming out. These books are gorgeous so I'll be very tempted at the prospect of replacing my tatty old paperback copy of 'The Mabinogion' (which I think I really need to read again), and it will clearly be the year to finally discover the weird fiction of Arthur Machen (The Great God Pan and Other Horror Stories).

It's the bicentenary of Emily Brontë's birth next year too, so there's an updated reissue of 'The Oxford Companion to The Brontë's'. I'm not the biggest Brontë fan, but even so this sounds desirable.

I'm still battling with Zola's 'The Sin of Abbé Mouret' (I will get there, but his take on rural life is both disturbing and heavy going. If ever there was a case of something nasty in the woodshed, and a man prepared to describe it in hysterical detail...) but that's not putting me off a sense of excitement about 'His Excellency Eugène Rougon'. I'm hoping Zola on court and political circles will be as good as Zola in 'Money'.

And finally, the book I'm really excited about. 'The Scarlet Pimpernel' is getting the World's Classics treatment. I have mentioned before how obsessed with this book I was aged about 11. I read it time after time, and whilst my enthusiasm for it has abated somewhat I'm still fond of it, I have never looked forward to reading the introduction of a book more.

Saturday, October 21, 2017

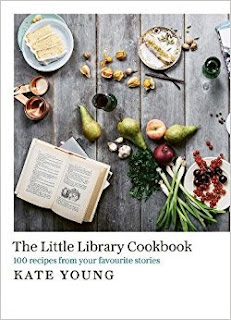

The Little Library Cookbook - Kate Young

I've occasionally read Kate Young's Guardian column where she matches recipes to books, but never got particularly excited about it - mostly because I was never particularly excited by the books that were featured when I saw it. Nevertheless I was quite excited when I saw a book was coming, and had put it in my wish list hoping someone might consider it as a Christmas present. Then yesterday I finally saw a copy (it's not made it to Leicester's Waterstones, but it was everywhere in London where I'd been wine tasting) and decided I really couldn't wait to get it.

I love the concept of matching books with food and drink (as demonstrated by the 100 odd books and booze posts to date that I've done here) finding that it adds another layer to your memories of a beloved book, and clear inspiration in the kitchen. I like the project element of it too as you search for just the right recipe to make the moment live.

Sometimes the choice is obvious, sometimes the links between text and food (or drink) are more personal. The most obvious food in literature is probably Proust's Madeleines (for which Young does indeed provide a recipe), but Edmunds's love for Turkish delight in 'The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe' must run a close second (recipe also included) and I bet it's a book that far more people have read.

Altogether there are 100 recipes divided by the time of day they might be eaten, some are things to make on a lazy weekend when there are hours to spare for pottering around making Marmalade (Paddington) and cinnamon buns (inspired by Donna Tartt's 'The Goldfinch'), or suggestions for porridge (The Secret Garden) which can be part of any but the most rushed morning routine. Also, and I wholeheartedly agree with Young on this, porridge doesn't have to be confined to breakfast.

And if you're thinking porridge isn't really worthy of a recipe, or that people these days are all too inclined to fill cookbooks with things that are scarcely recipes at all, then at least here it makes sense, because this is as much about a love of books, and a genuine love of food, as it is the recipes. It's a deeply engaging combination which provides a reading list as well as a recipe list, and encouragement to find the same kind of links in the books I too love.

I love the concept of matching books with food and drink (as demonstrated by the 100 odd books and booze posts to date that I've done here) finding that it adds another layer to your memories of a beloved book, and clear inspiration in the kitchen. I like the project element of it too as you search for just the right recipe to make the moment live.

Sometimes the choice is obvious, sometimes the links between text and food (or drink) are more personal. The most obvious food in literature is probably Proust's Madeleines (for which Young does indeed provide a recipe), but Edmunds's love for Turkish delight in 'The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe' must run a close second (recipe also included) and I bet it's a book that far more people have read.

Altogether there are 100 recipes divided by the time of day they might be eaten, some are things to make on a lazy weekend when there are hours to spare for pottering around making Marmalade (Paddington) and cinnamon buns (inspired by Donna Tartt's 'The Goldfinch'), or suggestions for porridge (The Secret Garden) which can be part of any but the most rushed morning routine. Also, and I wholeheartedly agree with Young on this, porridge doesn't have to be confined to breakfast.

And if you're thinking porridge isn't really worthy of a recipe, or that people these days are all too inclined to fill cookbooks with things that are scarcely recipes at all, then at least here it makes sense, because this is as much about a love of books, and a genuine love of food, as it is the recipes. It's a deeply engaging combination which provides a reading list as well as a recipe list, and encouragement to find the same kind of links in the books I too love.

Monday, October 16, 2017

#MeToo

I'vet been thinking about writing this post all day (because what Monday really needs is intensive thinking about sexual assault and misogyny) and wondering if it was really something I wanted to do. These are not memories I particularly want, and not things I would generally share outside of an actual face to face conversation- and maybe that's part of the problem.

So there was the young male teacher who wanted to be everybody's friend , he was young enough to have gone out with the only slightly older sister of one of my classmates, and not above referring to his ex in a derogatory way in class. I thought he was an arse, and someone I'd rather avoid. He told my mother, during parents evening, that he thought I'd probably been abused. I hadn't, it didn't make me warm to him. He told me, in front of a staff room full of collegues and another of my glass mates that he thought I was manipulative. It was probably my first experience as an almost adult of that feeling of shock and powerlessness that is never the reaction you expect to have.

At university on an almost empty campus at the end of first year there was the builder who walked up to me, in the middle of the day, and simply grabbed my breast and laughed about it with his friend. Again, total shock. What do you say, who do you tell, who actually cares, and what the hell does somebody who thinks that's alright do next? I didn't tell anyone, couldn't have accurately described either man, simply didn't know what to do.

There was a customer when I worked in a bookshop, in the days before we talked about grooming, who would come in and initiate friendly conversation about books. He was very softly spoken so you had to lean in to hear him, but he seemed harmless enough until one day he just started talking filth. Total panic again trying to work out what reaction he expected and wanted. It seemed he wanted a reaction, but that not giving him one was encouragement for him to continue. I confided in an older, female colleague - her reaction; how do you think it makes Me feel that he's harassing You. Jealous apparently. It turned out that 'Eddie' had made a habit of doing this in every bookshop in town. He stopped coming into our shop after another male colleague recognised him as his sisters maths teacher. It was his relative anonymity that had made his behaviour possible. Now I'd call the police there and then, at the time I couldn't bring myself to repeat the things he'd said.

There was the manager at work who had an escalating drink problem, not good in an off licence, he also had wandering hands when he'd been drinking, and a line in humour that it was hard to find funny. The situation came to a head when he verbally harassed a colleague young enough to be his daughter (in front of a group of us) and she asked me to back her up when she made an official complaint. There was a lot of pressure (from our female line manager) on us to drop the complaint, enough that it would have been easier to give in. I was asked to get everybody to make statements about his behaviour, assured they would be confidential, then after they were submitted, told that in fact they weren't confidential and that this man would have access to all of them.

He was dismissed, but not for harassment, he hadn't been paying for the stock he was drinking. When I applied for his job, the job I'd been doing whilst he was incapable of it, and the job I was expected to do whilst he was suspended and replaced, I was told I wouldn't get it because I couldn't be seen to be rewarded for reporting him. It was not a nice time and I'm still grateful for the many male colleagues who did provide support - because happily it isn't all men.

I seldom wear a watch now after being followed across town by a man who initiated conversation after asking the time (it's a common approach). Despite increasingly explicit requests for him to leave me alone he followed me for about quarter of an hour, from the street door of my flat, with a constant stream of verbal harassment, only stopping when I reached the high street and there were to many people to close for him to carry on unnoticed. After a couple of taxi journeys when similar things happened I'm now reluctant to get taxis at all.

And my list could go on, and on. Some incidents far more serious than any of these, dozens which are the common currency of women's lives (not just women at that) and hardly make an impression any more. But they should, and they should be talked about because I find the thing that bothers me most about #MeToo is how bad we are at talking about this kind of thing. I think about how poorly prepared I was to deal with any of the incidents that happened to me in my teens and twenties. How many times you're told that it's nothing, made to feel that complaining will be more trouble than it's worth, pressured not to complain because of the administrative problems it will create. Asked to consider the impact a complaint would have in the man involved, was his transgression serious enough to warrant the possibility of losing his job - and the guilt that makes you feel.There's the disbelief too, and all the rest of the toxic crap that gets thrown at you.

There's also the reality of complaining and following it through. I once went to court with a friend to support her whilst she got a restraining order against an ex who was stalking her. Listened whilst his lawyer attacked her on the stand, even asking if his client would give her children would she reconsider her position. That's how far he was from accepting that she simply didn't want to see him any more.

Most of all though, it's the horrible feeling of shocked disbelief that this is happening (again), the realisation that you won't react the way you always thought you would, won't know what to say or do, and that (again) your power over a situation has been removed from you. It's humiliating and frightening, and can take a long time to get over.

Sunday, October 15, 2017

The Third Eye - Ethel Lina White

Mid October and I feel stuck between the end of summer - it's been unseasonably warm this weekend - and the looming threat of Christmas which isn't actually that far away, despite protestations from some quarters that it's still to soon to talk about it. It isn't to soon, and even as I type I have Christmas puddings gently steaming in the kitchen.

I read 'The Third Eye' back in June, and haven't quite got round to writing about it in all the time since, finally doing it has definitely made me realise that this is really Autumn, and not the end of summer. Fortunately it's an excellent autumn book, with just the right atmosphere for darkening nights.

Caroline has been living with her sister and her family in a small London flat, she's welcome, but feels strongly that it's time she struck out independently. Partly because she feels slightly inadequate next to her far more intellectual sister, and her professor husband, and maybe because the professor is a little too fond of her.

There's no hint of impropriety, but rather a gentle reminder to the reader that no marriage, however sound, needs a permanent house guest in any form, much less that of a younger more physically attractive sister. It's part of White's charm that she reminds us of that before it's perhaps altogether evident to her characters.

Anyway, Caroline is happy to accept a post as games mistress at the Abbey School, despite her brother in laws reservations. Turning up at the beginning of the autumn term it's down becomes clear that all is not quite as it should be. The previous games mistress died in slightly odd circumstances, the matron has a bit of a cult following amongst the pupils, and holds séances with the headmistress. There's a general atmosphere of uneasiness that becomes increasingly tense - which is White's forte, and she really excelled at it here.

Caroline is soon affected by the same creeping unease that pervades the place, and her situation gets worse when she falls out with the matron over her treatment of a pupil. A crisis point is reached where Caroline finds herself in real danger from an unexpected source (after a wonderful exercise in rising paranoia and dread during a journey back to the school), before everything is resolved more or less satisfactorily (at least for Caroline).

It's an excellent book by an oddly neglected writer - there's this from Greyladies, and a few of her stories in the British Library Crime Classics anthologies, and whilst more of her work isn't hard to find as ebooks or print on demand formats, I feel she deserves more. This is the woman who wrote the book Hitchcock based 'The Lady Vanishes' on after all. 'The Third Eye' has a tremendous amount of atmosphere, as well as a plot that nicely blends a sense of impending melodrama with a feeling that these kind of things could all to easily happen. And it really is just the kind of thing to read with curtains drawn, and fire lit (or puddings steaming) on an autumn evening. It'll certainly make you think twice about talking to strangers on buses.

I read 'The Third Eye' back in June, and haven't quite got round to writing about it in all the time since, finally doing it has definitely made me realise that this is really Autumn, and not the end of summer. Fortunately it's an excellent autumn book, with just the right atmosphere for darkening nights.

Caroline has been living with her sister and her family in a small London flat, she's welcome, but feels strongly that it's time she struck out independently. Partly because she feels slightly inadequate next to her far more intellectual sister, and her professor husband, and maybe because the professor is a little too fond of her.

There's no hint of impropriety, but rather a gentle reminder to the reader that no marriage, however sound, needs a permanent house guest in any form, much less that of a younger more physically attractive sister. It's part of White's charm that she reminds us of that before it's perhaps altogether evident to her characters.

Anyway, Caroline is happy to accept a post as games mistress at the Abbey School, despite her brother in laws reservations. Turning up at the beginning of the autumn term it's down becomes clear that all is not quite as it should be. The previous games mistress died in slightly odd circumstances, the matron has a bit of a cult following amongst the pupils, and holds séances with the headmistress. There's a general atmosphere of uneasiness that becomes increasingly tense - which is White's forte, and she really excelled at it here.

Caroline is soon affected by the same creeping unease that pervades the place, and her situation gets worse when she falls out with the matron over her treatment of a pupil. A crisis point is reached where Caroline finds herself in real danger from an unexpected source (after a wonderful exercise in rising paranoia and dread during a journey back to the school), before everything is resolved more or less satisfactorily (at least for Caroline).

It's an excellent book by an oddly neglected writer - there's this from Greyladies, and a few of her stories in the British Library Crime Classics anthologies, and whilst more of her work isn't hard to find as ebooks or print on demand formats, I feel she deserves more. This is the woman who wrote the book Hitchcock based 'The Lady Vanishes' on after all. 'The Third Eye' has a tremendous amount of atmosphere, as well as a plot that nicely blends a sense of impending melodrama with a feeling that these kind of things could all to easily happen. And it really is just the kind of thing to read with curtains drawn, and fire lit (or puddings steaming) on an autumn evening. It'll certainly make you think twice about talking to strangers on buses.

Wednesday, October 11, 2017

At My Table - Nigella Lawson

Autumn, season of celebrity biographies, big name cookbooks, and sundry other Christmas hopefuls is upon us with a vengeance. There's a few food titles I'm hoping I might get for Christmas (Ren Behan's Honey and Rye, Kate Young's The Little Library Cookbook, and Supra by Tiko Tuskadze - which has been out a little longer, and looks excellent if anyone wants to know) and others that I've bought already.

'At My Table' was an impulse purchase when I saw it half price in Waterstones*. I've been a Nigella fan since 'How to be a Domestic Goddess' and love all of her earlier books. I've been less enthusiastic about the later books, but I think that's natural - Lawson is one of those bankable names who seems to be expected to produce something annually, and I'm not sure how sustainable that is - you just can't write a How to Eat, or a How to be a Domestic Goddess every damn year.

That and personal tastes change. How I cook and eat has certainly changed a lot over the last few years. Annoying shift patterns make it far harder to prepare, plan, or make meals, than it used to be. The food my partner prefers (both to prepare and eat) is different to my first choices as well. I like his cooking, I like him cooking and me not having too, but it does change the amount of time I used to spend playing in the kitchen (but then why should I have all the fun?).

All of which is a long winded way of saying I wasn't sure I'd like this book until I actually saw it. There are things I'd never make in here (toasted Brie and fig sandwich because I loathe Brie and am ambivalent about figs) but not many, because mostly these are exactly the sort of recipes I want at the moment.

Chicken and pea traybake, Hake with bacon peas and cider, the herbed leg of lamb, and the no churn ice creams all look great (those were the things that caught my eye during the flick test). It's a book full of recipes that don't need to much thinking about beforehand, and which don't demand to much effort to produce - recipes that a tired person can tackle with enthusiasm on a Friday night after a long week and a very quick trip around a supermarket. Or look forward to whilst they slowly do their thing in an oven and you try and catch up on all the tedious chores that seem to make up weekends at the moment.

It's exactly the sort of home cooking I'm after (the emergency brownies which come in small quantities sound intriguing as well, I'm not sure any brownie recipe will ever quite supplant the HtbaDG version, but that one is built on industrial lines - this one isn't.) Apparently some people have been sniffy about a whipped feta recipe, but hands up, it's not something that had ever occurred to me to do and I like the sound of it a lot.

On the whole a great book for beginner cooks, harassed cooks, and cooks (like me) who feel they've lost a bit of their kitchen mojo and want some inspiration.

*Why are the books everyone is likely to buy anyway always so heavily discounted? 'At My Table' has a cover price of £26, which I imagine very few people will pay. Buying it for £13, or less, makes the books listed above look unattractively expensive by comparison, and doesn't make it any easier to understand what a book actually needs to cost.

Monday, October 9, 2017

The Cocktail Book

'The Cocktail Book', reprinted here by the British Library, first appeared in 1900, and it seems to have been the first book specifically dedicated to the cocktail (there are earlier books which cover Cocktails along with other things, this book is just Cocktails).

This edition is a nice little hardback with a smart black and gold cover which has almost certainly been designed as a stocking filler, and thought of as a bit of a curiosity, but especially after my cocktail experiments back in August (which also celebrated the BL's Crime Classics series, matching drinks to books gives a nice set of boundaries to work within!) I've found I have a lot of time for these early drinks books (Jerry Thomas' Bartenders guide, Ambrose Heath's 'Good Drinks', and Harry Craddock's 'Savoy Cocktail Book' are the others I have). They are far more than curiosities.

The great thing about these books is that a lot of the drinks are easy to mix, there are plenty which don't call for lots of obscure and expensive ingredients, and lots of them taste good (some might not, tastes and times change). Each also have their particular strengths, for 'The Cocktail Book' it's the use of bitters.

Angostura Bitters are easy to find, most supermarkets sell them, but they're only the tip of an aromatic (and bitter) iceberg. Bitters are useful things to have around, they can transform drinks in all sorts of interesting ways, so a book that encourages their use is a good thing (it'll mostly be a case of searching them out online for most of us, but they're not particularly expensive, and go a long way). There is also a handy glossary at the back of this book which explains what the less familiar things are, and where practical what to substitute them with.

As a curiosity it's certainly interesting to see the kind of drinks that were popular in the Belle Époque, and though ingredients like acid phosphate are a challenge to source (it's available on Amazon in the U.S, but looks like it would take more searching for in the U.K) things like Café Kirsch (coffee and kirsch shaken over ice - though I prefer it warm) are both simple and appealing.

However you look at it, it's a book with plenty to offer, and well worth investigating.

Angostura Bitters are easy to find, most supermarkets sell them, but they're only the tip of an aromatic (and bitter) iceberg. Bitters are useful things to have around, they can transform drinks in all sorts of interesting ways, so a book that encourages their use is a good thing (it'll mostly be a case of searching them out online for most of us, but they're not particularly expensive, and go a long way). There is also a handy glossary at the back of this book which explains what the less familiar things are, and where practical what to substitute them with.

As a curiosity it's certainly interesting to see the kind of drinks that were popular in the Belle Époque, and though ingredients like acid phosphate are a challenge to source (it's available on Amazon in the U.S, but looks like it would take more searching for in the U.K) things like Café Kirsch (coffee and kirsch shaken over ice - though I prefer it warm) are both simple and appealing.

However you look at it, it's a book with plenty to offer, and well worth investigating.

Sunday, October 8, 2017

Was there a Russian Jane Austen and What's a Classic anyway?

I have been reading books (though slowly) and I will write about one soon, but this morning I read This article on The Pool website by Viv Groskop and it's been bothering me all day. In it she asks how do we acknowledge that men created the majority of the literary classics without doing women writers a disservice.

Classic seems to be a fairly elastic term at the best of times but I'm sceptical about this article and it's statement that "It's simply not as if there are dozens of women writers from the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries who remain unknown and under-rated" or that "Many of the great male writers attained their status because they said something about the time they were living in that was viewed as significant".

It may well be that there aren't many British women writers from the 18th, 19th, and 20th century remaining to be discovered, but the list of 'anomalies' is far longer than Woolf, Austen, assorted Brontës, George Eliot, Mary Shelley, Elizabeth Gaskell, and Louise May Alcott (sic). Just looking at my Penguin and Oxford classics I can add Fanny Burney, Maria Edgeworth, Francis Hodgson Burnett, Mary Elizabeth Braddon, Mrs Oliphant, and Ellen Wood to that list. I have something over 400 Virago Modern Classics, dozens of Persephone's, yards of golden age Crime by the acknowledged queens of the genre, and all sorts of other things to carry on making the point with.

All of them were popular in their day, presumably because they too were saying something significant about the time they were living in. Books in the U.K. are relatively cheap and we're well served with reprints of English language books. My by no means comprehensive collection tells me that these women were far from anomalies, and that it's quite possible to acknowledge that they were unjustly neglected, or dropped from the canon, over the years without doing any disservice to their male counterparts who were justly recognised and remembered.

We are not so well served by books in translation, and I have no idea if there are French, Italian, Russian (you get the idea) versions of Virago or Persephone, intent on rescuing those hidden female voices, but if books by Irene Nemirovsky or Teffi have started to appear in English over the last decade or so, I'm prepared to believe there are more (Wikipedia leads me to suppose so too).

I'm also wondering how many of those canonical classics by the great male writers that fill so many bookshelves are read as opposed to representing good intentions. Their names may be better known, but outside of universities how many people really settle down with Chekhov at the end of a long day? (Readers here are not likely to be a representative sample for answering that question).

To me it seems that where we do do those great male writers a disservice is in isolating them from their female peers. I've got far more out of reading Trollope having read Oliphant's 'Carlingford Chronicles', and enjoy Wilkie Collins more for having read Braddon - and that's a list that could go on too.

Classic seems to be a fairly elastic term at the best of times but I'm sceptical about this article and it's statement that "It's simply not as if there are dozens of women writers from the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries who remain unknown and under-rated" or that "Many of the great male writers attained their status because they said something about the time they were living in that was viewed as significant".

It may well be that there aren't many British women writers from the 18th, 19th, and 20th century remaining to be discovered, but the list of 'anomalies' is far longer than Woolf, Austen, assorted Brontës, George Eliot, Mary Shelley, Elizabeth Gaskell, and Louise May Alcott (sic). Just looking at my Penguin and Oxford classics I can add Fanny Burney, Maria Edgeworth, Francis Hodgson Burnett, Mary Elizabeth Braddon, Mrs Oliphant, and Ellen Wood to that list. I have something over 400 Virago Modern Classics, dozens of Persephone's, yards of golden age Crime by the acknowledged queens of the genre, and all sorts of other things to carry on making the point with.

All of them were popular in their day, presumably because they too were saying something significant about the time they were living in. Books in the U.K. are relatively cheap and we're well served with reprints of English language books. My by no means comprehensive collection tells me that these women were far from anomalies, and that it's quite possible to acknowledge that they were unjustly neglected, or dropped from the canon, over the years without doing any disservice to their male counterparts who were justly recognised and remembered.

We are not so well served by books in translation, and I have no idea if there are French, Italian, Russian (you get the idea) versions of Virago or Persephone, intent on rescuing those hidden female voices, but if books by Irene Nemirovsky or Teffi have started to appear in English over the last decade or so, I'm prepared to believe there are more (Wikipedia leads me to suppose so too).

I'm also wondering how many of those canonical classics by the great male writers that fill so many bookshelves are read as opposed to representing good intentions. Their names may be better known, but outside of universities how many people really settle down with Chekhov at the end of a long day? (Readers here are not likely to be a representative sample for answering that question).

To me it seems that where we do do those great male writers a disservice is in isolating them from their female peers. I've got far more out of reading Trollope having read Oliphant's 'Carlingford Chronicles', and enjoy Wilkie Collins more for having read Braddon - and that's a list that could go on too.

Saturday, October 7, 2017

Books I'd love to see on Screen

I've been out in the villages today so have missed National bookshop day, but as I'm no stranger to the inside of a bookshop I don't feel to badly about it, and there's always tomorrow. Meanwhile a comment from Susanna about Arnold Bennett's 'The Grand Babylon Hotel' got me thinking about that perennial question; what books would you most like to see adapted for television?

I believe there's yet another Jane Austen adaptation on its way, which I'll almost certainly watch, and probably enjoy. And I might have read about a Brontë something or other which I would also watch but with a little less enthusiasm (and also I might have imagined reading about this). I'd also add Agatha Christie to the over adapted list.

Meanwhile, Susanna is right, 'The Grand Babylon Hotel' would make excellent T.V. It's a big, colourful, romp with plenty of action, and scope for gorgeous costumes. It also breaks conveniently into 2 parts, and I'd happily watch it.

I'd also quite like to see Georgette Heyer on the television, possibly something late like 'Cousin Kate' (though its depiction of mental health issues might be problematic). The late books are generally rather less loved than the early ones, so much less danger of howling in outrage at whatever nonsense is on the screen (the really awful David Walliams take on Tommy and Tuppance comes to mind). 'Cousin Kate' (thinking about re reading it for the 1968 book club) has an oppressive, somewhat gothic atmosphere, the orphaned Kate is struggling to find a way to keep herself when she's taken in by her half aunt. There's something wrong in the house but she's not clear what it is, but when a mutilated rabbit turns up we can all guess what's coming next. Done properly it could be good.

Given the success of Elizabeth Gaskell's 'Cranford' books it's a safe bet there would be an audience for Margaret Oliphant's Carlingford Chronicles too. I love these books, not least because of the way she responds to Trollope's Barchester Chronicles in them (though that's by no means all she's doing). They absolutely deserve to be better known, and have some tremendous characters in them.

I'd really like to see some of Barbara Pym's excellent women given some screen space too. They deserve the attention, and done well would be wonderful to watch.

Meike Ziervogel's 'The Photographer', or Marie Sizun's 'Her Father's Daughter' (published by Meike's Peirene Press) would also be great. They both take a good look at fathers returning from the Second World War. 'The Photographer' is a loosely biographical account of a family from East Germany being drawn into the war, partly through an act of betrayal, and finally finding each other again in the refugee camps of the west. 'Her Father's Daughter' is French, the betrayal is of a different nature, and how families fit together again after long periods of separation is the major theme. Both books are brilliant, both offer a different view of the impact the war had on society to the one I'm used to seeing. Both would make for tense and gripping on screen drama.

I believe there's yet another Jane Austen adaptation on its way, which I'll almost certainly watch, and probably enjoy. And I might have read about a Brontë something or other which I would also watch but with a little less enthusiasm (and also I might have imagined reading about this). I'd also add Agatha Christie to the over adapted list.

Meanwhile, Susanna is right, 'The Grand Babylon Hotel' would make excellent T.V. It's a big, colourful, romp with plenty of action, and scope for gorgeous costumes. It also breaks conveniently into 2 parts, and I'd happily watch it.

I'd also quite like to see Georgette Heyer on the television, possibly something late like 'Cousin Kate' (though its depiction of mental health issues might be problematic). The late books are generally rather less loved than the early ones, so much less danger of howling in outrage at whatever nonsense is on the screen (the really awful David Walliams take on Tommy and Tuppance comes to mind). 'Cousin Kate' (thinking about re reading it for the 1968 book club) has an oppressive, somewhat gothic atmosphere, the orphaned Kate is struggling to find a way to keep herself when she's taken in by her half aunt. There's something wrong in the house but she's not clear what it is, but when a mutilated rabbit turns up we can all guess what's coming next. Done properly it could be good.

Given the success of Elizabeth Gaskell's 'Cranford' books it's a safe bet there would be an audience for Margaret Oliphant's Carlingford Chronicles too. I love these books, not least because of the way she responds to Trollope's Barchester Chronicles in them (though that's by no means all she's doing). They absolutely deserve to be better known, and have some tremendous characters in them.

I'd really like to see some of Barbara Pym's excellent women given some screen space too. They deserve the attention, and done well would be wonderful to watch.

Meike Ziervogel's 'The Photographer', or Marie Sizun's 'Her Father's Daughter' (published by Meike's Peirene Press) would also be great. They both take a good look at fathers returning from the Second World War. 'The Photographer' is a loosely biographical account of a family from East Germany being drawn into the war, partly through an act of betrayal, and finally finding each other again in the refugee camps of the west. 'Her Father's Daughter' is French, the betrayal is of a different nature, and how families fit together again after long periods of separation is the major theme. Both books are brilliant, both offer a different view of the impact the war had on society to the one I'm used to seeing. Both would make for tense and gripping on screen drama.

Wednesday, October 4, 2017

The Grand Babylon Hotel - Arnold Bennett

I've been meaning to investigate Arnold Bennett for a long time, and found this in Edinburgh back in January. It sounded entertaining so seemed like a good place to start.

The back blurb told me that:

The Times also described it as rather excellent.

It is excellent. Nella, and Theodore Racksole are an appealing pair, with a delightfully modern relationship for a book first published in 1902, Theodore let's Nella do much as she likes, and what he's told, on the grounds that it's just easier that way, and as she's a determined young woman he's probably right.

From the very night that he buys the Hotel, Theodore suspects something is amiss, and relishes the chance to solve the problem. The mix of Ruritanian style royalty, murder, mayhem, kidnap, and international intrigue is entirely far fetched and very much tongue in cheek, which is all extremely satisfying and great fun along the way.

'The Grand Babylon Hotel' seems to be a bit of an oddity in Bennett's oeuvre - it certainly has little to do with the potteries and the five towns, and sounds worlds away from the 'Old Wives Tale' as well. If I'd realised that earlier it probably wouldn't have been the book I started with- simply because it was so much fun that I'd quite like more of the same. Beginning with something more typical might have been a better idea, if only because at the moment I still don't really feel I know anything about Bennett. That will change though, and meanwhile this one is a little gem of a thing.

The back blurb told me that:

"Nella, daughter of millionaire Theodore Racksole, orders a dinner of steak and beer at the exclusive Grand Babylon Hotel in London. Her unladylike order is refused, so Theodore promptly buys the chef, the kitchen, and the whole hotel. But when staff begin to vanish and an aristocratic guest goes missing, Nella discovers that murder, blackmail, and kidnapping are also on the menu."

The Times also described it as rather excellent.

It is excellent. Nella, and Theodore Racksole are an appealing pair, with a delightfully modern relationship for a book first published in 1902, Theodore let's Nella do much as she likes, and what he's told, on the grounds that it's just easier that way, and as she's a determined young woman he's probably right.

From the very night that he buys the Hotel, Theodore suspects something is amiss, and relishes the chance to solve the problem. The mix of Ruritanian style royalty, murder, mayhem, kidnap, and international intrigue is entirely far fetched and very much tongue in cheek, which is all extremely satisfying and great fun along the way.

'The Grand Babylon Hotel' seems to be a bit of an oddity in Bennett's oeuvre - it certainly has little to do with the potteries and the five towns, and sounds worlds away from the 'Old Wives Tale' as well. If I'd realised that earlier it probably wouldn't have been the book I started with- simply because it was so much fun that I'd quite like more of the same. Beginning with something more typical might have been a better idea, if only because at the moment I still don't really feel I know anything about Bennett. That will change though, and meanwhile this one is a little gem of a thing.

Monday, October 2, 2017

Back home with Books

Back home, and back to work. Work looked like I must have been gone a month rather than a week, which I suppose at least makes it abundantly clear how much I actually do do there. I can hope that's been noticed (though due to being both busy, and chronically short staffed, it's unlikely) because one day in I'm feeling in need of another break.

Inverness was fun and quite busy so we took our time coming home, stopping in the Borders on Saturday before the last stretch down the M1. I love the Borders, and have a particular fondness for St Boswells (pretty village, excellent bookshop - The Main Street Trading Company with a decent Café) so staying there was a proper treat.

Packing for this trip, I made the mistake of taking 2 books I really felt I ought to finish but just haven't been in the mood for, so ended up doing very little reading. It was only on Saturday afternoon that I saw sense and decided to actually read one of the handful of new books I'd bought.

The unread books (I will finish them soon) are Zola's 'The Sin of Abbé Moret' which I started months ago. The problem is the middle section, it's almost unbearably dull - a long list of plant names, interspersed with an equally tedious sexual awakening. I'll grit my teeth and get on with it at the weekend, but Zola on the countryside is not a treat. The other book is L. M. Montgomery's 'Anne of the Island'. I love Montgomery, I loved the Anne books as a child (all of them) and have been looking forward to reading the Virago reprints. Montgomery is far better on nature than Zola, but the combination was not a happy one, so Anne needs to wait a little longer.

My book buying was fairly restrained, partly held back by the tottering piles of unread books currently infesting every part of my flat. They're becoming overwhelming again and I need to do something about it, but I still couldn't resist 'The Journal of Marie Bashkirtseff' ( begun age 12, ends with her death at 25, she was born in the Ukraine in 1859, but mostly grew up in France. She wanted to be a singer, but TB stopped that so she turned to painting. She founds remarkable, the book is a doorstop, but it'll keep) or 'Cork on the Water' by MacDonald Hastings (fishing, shooting, and murder, with ballerinas - it sounded worth a punt) both from Leakey's. E. F. Benson's 'Secret Lives' was a charity shop find, as Benson has never yet disappointed I'm pleased to have found this.

Mindful of the just one book principle of supporting both bookshops and publishers I found 'The Nebuly Coat' (Apollo it sounds intriguing, full of melodrama and architecture, which are both things I like) and Alistair Moffat's 'The Reivers' in the Main Street bookshop. I also found an excellent toasted coconut cake there that I'd very much like the recipe for. I'm reading The Reivers at the moment and thoroughly enjoying it.

Inverness was fun and quite busy so we took our time coming home, stopping in the Borders on Saturday before the last stretch down the M1. I love the Borders, and have a particular fondness for St Boswells (pretty village, excellent bookshop - The Main Street Trading Company with a decent Café) so staying there was a proper treat.

Packing for this trip, I made the mistake of taking 2 books I really felt I ought to finish but just haven't been in the mood for, so ended up doing very little reading. It was only on Saturday afternoon that I saw sense and decided to actually read one of the handful of new books I'd bought.

The unread books (I will finish them soon) are Zola's 'The Sin of Abbé Moret' which I started months ago. The problem is the middle section, it's almost unbearably dull - a long list of plant names, interspersed with an equally tedious sexual awakening. I'll grit my teeth and get on with it at the weekend, but Zola on the countryside is not a treat. The other book is L. M. Montgomery's 'Anne of the Island'. I love Montgomery, I loved the Anne books as a child (all of them) and have been looking forward to reading the Virago reprints. Montgomery is far better on nature than Zola, but the combination was not a happy one, so Anne needs to wait a little longer.

My book buying was fairly restrained, partly held back by the tottering piles of unread books currently infesting every part of my flat. They're becoming overwhelming again and I need to do something about it, but I still couldn't resist 'The Journal of Marie Bashkirtseff' ( begun age 12, ends with her death at 25, she was born in the Ukraine in 1859, but mostly grew up in France. She wanted to be a singer, but TB stopped that so she turned to painting. She founds remarkable, the book is a doorstop, but it'll keep) or 'Cork on the Water' by MacDonald Hastings (fishing, shooting, and murder, with ballerinas - it sounded worth a punt) both from Leakey's. E. F. Benson's 'Secret Lives' was a charity shop find, as Benson has never yet disappointed I'm pleased to have found this.

Mindful of the just one book principle of supporting both bookshops and publishers I found 'The Nebuly Coat' (Apollo it sounds intriguing, full of melodrama and architecture, which are both things I like) and Alistair Moffat's 'The Reivers' in the Main Street bookshop. I also found an excellent toasted coconut cake there that I'd very much like the recipe for. I'm reading The Reivers at the moment and thoroughly enjoying it.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)