Monday, August 30, 2021

Simple Fire; Selected Short Stories - George Mackay Brown, edited by Malachy Tallack

Thursday, August 26, 2021

The Black Moth - Georgette Heyer

I've been reading this book as part of the Georgette Heyer Readalong on Twitter, where we have mixed feelings about it but have raced ahead to the end because I wanted to write about it today - the publication day for the centenary edition hardback.

I'm in the enjoying the book for what it is camp, and what it is, is quite remarkable. Georgette Heyer was 19 when she published this, her first novel. Written to entertain her brother whilst he was ill it was presumably told rather than read, to begin with, which I think might have some bearing on how certain parts read now. I'm also assuming that it was based on books, plays, and films that were Heyer family favourites. 'The Black Moth' has remained in print for all of its 100-year life span.

It isn't Heyer's best work - it hardly could be given that she went on to write for another 50 years - it certainly isn't her worst (I have a feeling that might be the suppressed 'The Great Roxhythe' of which I once read a few pages online and quickly gave up on). For a first book by a teenager, it's amazing though, full of prototypes that would later become Heyer standards and indicators of how very good a writer she would be.

The plot is fairly lightweight and thoroughly over the top - the lost heir to an Earldom is terrorising the roads of southern England disguised as a highwayman (though he will not attack women, children, or old men) after everybody thought he cheated at cards. His younger brother is feeling bad about it and dealing with an expensive and capricious wife. His wife's brother is merrily plotting to kidnap and rape every nice young woman he meets (when he's not trying to borrow money) and somehow it all works out happily after a comedy Irishman turns up in deepest Sussex.

The Irishness of Sir Miles O'Hara JP is one of the things that was probably hilarious read in a family circle in 1921, but which doesn't work particularly well in a book group discussion now (apart from anything else it doesn't make a lot of sense). When Sir Miles makes an appearance I remind myself that Heyer was 19 when she wrote this. There are other issues that I'll come onto in a minute.

First, it seems worth spending a moment considering the excellence of this centenary edition. I wrote a post about this when I first got the book, and further acquaintance with it has only improved my opinion. I would love to see all of Heyer's books get this treatment. I'm old enough to appreciate the larger type as well as the handsome cover. I really appreciate the introduction, after-words, and the classification of her other titles.

The latter is a particularly nice touch if you're newly navigating these books - pro tip, the classic adventures (Beauvallet, Royal Escape, An Infamous Army, and the Spanish Bride) and the Medieval Classics (Simon the Coldheart, The Conqueror, and My Lord John) or best left to the committed fans. Or in the case of an Infamous Army and The Spanish Bride, to people with a real interest in the Penninsula Wars and the battle of Waterloo.

Phillipa Gregory's thoughtful introduction is probably my favourite thing (after the cover which I think is delicious) about this edition though. There's a lot to unpick, most of which I agree with, and some I'm not so sure about. Gregory makes the distinction that Heyer is creating historical fantasy rather than historical fiction (fair) and discusses how she doesn't write about the terrible poverty that followed the industrial revolution - but does have a heroine take a chimney sweep to the dentist amongst other examples (in another book).

In 'The Black Moth' there's an almost throw-away reference to a character being given a black page boy - a fashion statement in employees. The book is set in the 1750s so we know this probably means slave, later what I think is the same page boy presents her with a pet monkey which reinforces that perception, but Heyer makes no other comment about it. The result is we're left to do our own research and draw our own conclusions about the actual history, which is one of the things that really work about her books for me. When I first read this aged around 13 I knew very little about slavery, but it's a detail that always niggled, nothing could more effectively get me to learn.

Gregory says Heyer is categorically not a feminist, and this is where I'm not so sure. She's not a feminist in the contemporary sense, and while she pushes the boundaries of what a romance novel is her heroines still always meet a man that we hope they'll live happily ever after with - but even here in her first book there's a masterly description of the heroine (around Heyer's age) being pursued by a predatory older man that is instantly recognisable and could very easily have been a Me Too statement. It's also offered without comment, but in a story a teenage girl was telling her brothers.

This will be a constant theme in Heyer's writing, in book, after book, she describes the limitations imposed on women and exposes the hypocrisy in the double standards her heroines have to deal with. In her own life, she ended up supporting her mother, brothers, and for a long time her husband, with her writing. Heyer and her heroines worked within the constraints of her society, but I think she's pushing against its boundaries every time she points out the inherent unfairness of a situation and with the type of agency she gives her heroines. Maybe she wasn't a feminist, but she certainly made me into one.

So on the whole I have no hesitation in recommending this - it's fun on its own terms, although very much of its time - perhaps don't read it if you find old-fashioned attitudes about race offensive (there are some dodgy bits about what it's acceptable for rich men to get away with too). It's also fascinating to see how Heyer starts, understand the elements that were always present in her writing, and see how other things will develop through out her career. It is also, and this bears repeating, the Most Lovely edition.

Wednesday, August 25, 2021

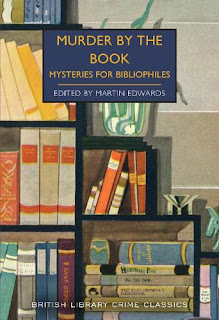

Murder by the Book - Edited by Martin Edwards

August has been remarkably kind to me this year right down to throwing some particularly nice review books my way. 'Murder by the Book, Mysteries for Bibliophiles' was waiting for me when I got back from Shetland, and whilst there were other things I should have read first I couldn't resist diving into it.

It was a sound decision, it's a collection that doesn't put a foot wrong as far as I'm concerned. This is partly because like the recent Guilty Creatures anthology the links to the overall theme are sometimes slight - it might be that a book is a clue or a writer is plotting no good, or that a mystery writer turns detective, occasionally the hapless writer is the victim. There are instances where the writers are clearly having considerable fun with their brief and others which throw some unexpectedly personal sidelights onto their writers.

It's also fair to say that I really enjoy books about books - the perfect companion volume to this is The Haunted Library edited by Tanya Kirk and also from the British Library team. It's got some (to me at any rate) genuinely scary stories in it, so 'Murder by the Book' would provide some light relief to go alongside it.

I was asked if I could focus on one particular story for this review; The Strange Case of the Megatherium Thefts' by S. C. Roberts, to which the answer was fair enough, yes. I did wonder what I'd do if I really didn't like it (could happen) but as it stands I enjoyed it a lot, and to my mind, it's one of the most interesting entries in the book - if not quite my favourite.

S. C. Roberts was a prominent bookman, Secretary to Cambridge University Press for a quarter of a century before becoming Master of Pembrooke College, and Vice-Chancellor of Cambridge University. He was also a committed Sherlock Holmes fan and a leading exponent of Sherlockian scholarship in this country (I'm shamelessly cribbing from the introduction here).

'The Strange Case of the Megatherium Thefts' was initially privately printed in 1945 and is an homage to Conan Doyle's style. It's a charming story and contains the only crime in the book that I could well imagine committing. I'm not alone in this as it was apparently inspired by a real-life crime in the Athenaeum Club. In it Holmes is consulted by a professor about the strange disappearance of a number of library books, who has been taking them, and why is duly revealed.

I have mixed feelings about writers using other authors' characters. We build up very personal ideas of who a character is, and too often in when another writer takes them on we get their vision and it isn't close enough to our own to be satisfying. There's also the Ask A Policeman risk. Here members of the Detection Club swapped characters between themselves creating affectionate but merciless parodies of each other's work. It's really enjoyable but I haven't been able to take Mrs. Bradley or Lord Peter Wimsey seriously since.

Roberts makes a good job of Holmes though, he does it with affection, a light touch, and without parody - it's a successful hommage. The bookish references multiply too which is what I really enjoyed here - there's the obvious co-opting of a fictional character, the bookish nature of the crime, and then there's the partial list of stolen books, which include Three Men in a Boat and The Wrong Box - it's a nice comic touch. (Those are the two I've read, both are comic masterpieces).

Tuesday, August 24, 2021

The Widow of Bath - Margot Bennett

In the end, this was the only book I managed to read whilst I was away - I had high hopes for getting through lots of things, but between the excitement of getting engaged (that's not going to get old for me any time soon) and trying to catch up with a few people and spend time with family and the friends I was travelling with time got away from me. That's as inevitable as the fact that I'd buy more books than I packed - so why do I even pack books plural?

'The Widow of Bath' was written in 1952 which my Crime Classics spreadsheet tells me is a vintage year as far as I'm concerned - there's a discernable shift between the war and immediate post-war period and the start of the 1950s when the mood and tone get distinctly darker. it's the difference between looking back and looking forward I think, and I wonder what our own post covid world will throw at us in this respect.

The book opens with Hugh Everton, determinedly drinking in a second rate hotel on the south coast where all is not quite as it should be, even for a post-war British seaside hotel. Before he knows quite where he's at he bumps into an ex-girlfriend, and then her aunt by marriage - a femme fatale with who he has also had an affair. She's accompanied by her husband, a couple of friends, and brings an atmosphere you could cut a knife with.

Hugh drifts along with her suggestion to come home with them, and before he knows it the husband, Judge Bath has been shot whilst the rest of the party were downstairs playing cards together. This is trouble for Hugh who has a shady sort of past, and whilst it's hard to see who could have done it, why can see plenty of reasons why people might want to have done it.

Up to his neck in it, Hugh starts investigating some of the loose ends around him, which mostly makes things worse, but as almost everybody seems intent on threatening him he doesn't really have a lot of choices. It's a clever book with a plot that at first seems surprisingly current (spoiler alert - it's about people smuggling) but which on reflection makes it clear that the state of the world hasn't changed as much as we might like in the last 70+ years.

It's also the kind of book I'd love to see get adapted for television, instead of yet another Agatha Christie getting pulled into a shape it doesn't really fit. You want contemporary issues with real darkness behind them in period costume - this is the perfect vehicle for it. Christie is a wonderful writer, but she's not the only one and this book is a cracker with real noir atmosphere and dialogue, along with some absolutely perfect scene-setting descriptions.

Bennet is a master at filling a reasonably well to do seaside town with a sense of menace, and the way she unravels Hugh Everton for us is brilliant. Martin Edwards compare Margot Bennett favourably to Raymond Chandler in his introduction - it's an assessment I heartily agree with.

Monday, August 23, 2021

A Short History of the World According to Sheep - Sally Coulthard

I read this one as part of a reading group, and more than a few chapters in a rush during a post-lunch dip on a Saturday afternoon when I was desperately trying to stay awake. This may have slightly coloured my view as it didn't do the best job of keeping me awake.

It's the kind of book that I think is meant to be bought mostly as a present, maybe for people who have just moved to the country. There are bits of it that are interesting, and Coulthard's style is engaging, but it's very light and when I went to chase up references they didn't amount to much. This coupled with some basic errors or things that were really vague made it hard to trust what I was reading - it's a stocking filler kind of book. Worth a read if you know nothing about sheep, textiles, or their respective histories, but frustrating if you do know a bit about them and want to know more.

I sort of enjoyed the punning chapter titles (Spinning a Yarn, Mills and Boom etc) but again they're perhaps an indicator that the book isn't meant to be taken tremendously seriously. I think if I'd read this quickly, perhaps on a wet afternoon with nothing else much available (and it also feels like the sort of book you might find on the shelf of the nicer kind of B&B) I would be kinder about it.

Reading it 3 chapters a week with a bunch of the most delightfully critical people you could hope to meet meant that between us I don't think we missed a single flaw! A quick look at amazon shows me a lot of really enthusiastic reviews as well, which is now making me feel slightly churlish, and I certainly enjoyed Coulthard's style enough to pick up another one of her books - I'd just make sure I read enough of it to be sure it was what I wanted before buying. So. Light, enjoyable enough if sheep have previously been a closed book, but not one for the in depth material.

Thursday, August 19, 2021

Aberdeen and Shetland

Today is my friend Clover's birthday, and she tells me it's not a proper summer without Shetland pictures, so these are basically for her, and my last photo dump now that the excitement of the last couple of weeks is starting to settle down. The Aberdeen pictures are mostly from around Kings College, Old Aberdeen, and Union Street.

The sign says Spital under the ivy, it's a very Scottish name, I've seen it in the Borders too, I love the tiled Aberdeen street signs, though a lot more of them have lost there pointing fingers since my student days there.

This well worn stone was part of a wheel house at Jarlshof.

Another view through a salty ferry window - we saw a fin whale not ling after this

Possibly the most photographed place in Shetland

Monday, August 16, 2021

News

I didn't mean to be quiet for so long, but it's been an eventful 10 days. I've been to Aberdeen and had a nostalgic wander around the university and some of the places I knew as a student. It felt like everything had changed except the pubs - every single one we used to drink in was still there with the same name, and in several cases what looked like minimal sprucing from the outside. It's good to know there are some constants in the world.

I made it up to Shetland for my father's birthday for the first time in almost 30 years which was lovely after the last 18 months - as we all get older living so far apart is harder. Whilst there we saw the last of the puffins, what felt like hot and cold running otters, seals, gannets, a grouse (exciting for Shetland) white-sided dolphins, porpoises, and a fin whale which was tremendously exciting. I had to look fin whales up, we saw this one from the ferry terminal in Unst, turns out it's the second biggest species going after Blue whales. We missed out on Orca's who kept a low profile all week and then started visiting every beach or headland we'd been near after we'd left them. A Fin whale is obviously a lot cooler though, so the Orca's can stick it.

Most exciting of all (for us anyway) is that my long term partner completely surprised me with a proposal, in what was (for us) the most romantic way I could imagine. I didn't know this was on the cards so I'm still a bit dazed by it all, also very happy, and feeling really lucky - hence the silence!

Wednesday, August 4, 2021

Broken Lights - Basil Ramsey Anderson

This is the second book from the Northus project and the first of the volume of poetry. Novels are much easier to write about which is one reason why it's taken me so long to get round to posting about Broken Lights, which even for poetry presents a few challenges for me to do justice to it.

Basil Ramsey Anderson died from tuberculosis when he was 26, another tragedy in a family that had more than their fair share of them. His younger brother had also died of tuberculosis only a couple of months before, His father and uncle had both drowned in a fishing accident when Basil was 5, leaving his mother, pregnant with her 6th child. 2 more of the 6 Anderson children also died from tuberculosis within a few years of Basil. Nothing could more clearly underline the poverty of the family, or the struggle Mrs. Anderson must have had than those losses.

When Basil was 14 the family moved to Leith in Edinburgh, where they became a part of an expatriate Shetland community there - which included the notable poet Jessie Saxby, both Saxby, and the Anderson family were from Unst, the farthest North island in Shetland - Unst is possibly the inspiration for the map of Treasure Island, Robert Louis Stevenson visited it to see the lighthouse on Muckle Flugga that his family built. It was Jessie Saxby who put together and edited Broken Lights after Basil's death. Edinburgh still has a community of Shetland-associated writers in it, including Robert Alan Jamieson who writes the introduction to this collection.

As a poet Basil Ramsey Anderson is a mixed bag, though it's reasonable to assume that had he lived longer he might have left a really considerable legacy. As it is we get something of a mixed bag. Robert Alan Jamieson makes a strong case for the poems in English and Scots as being better than they're sometimes considered. His argument is compelling, but the truth is that these are the works of a young man, edited by another hand, in a form of speech that wasn't entirely his own. The Anderson's learned to read in English but spoke in Shetland dialect, these poems are the work of someone finding their way. The rhymes come easily, and they're fashionably sentimental but on their own, they wouldn't be much of a legacy.

The Shetland dialect works are a different matter. There's only a dozen of them and Auld Maunsie's Crü is considered the masterpiece. I vaguely remember reading this in school, and understand it's still taught - which is brilliant. There's a confidence about the dialect poems, and a sense of identity, maybe even authenticity (although that's a loaded term these days) that underlines that Basil's early death was more than a loss to just Shetland literature and his friends.

And that's something else this collection does; show the depth of friendship for Basil, and that too is worth celebrating and remembering. Saxby was obviously fond of his, and there's a whole lot of verse (of varying quality) in her introduction from other friends which are at least a testament to the regard they held for Basil. They're also a testament to the wider community he was part of in Edinburgh. Some extracts from Basil's letters at the end of the book are another insight it's good to have - and again make me feel his lack of time more keenly.

The glossary of Shetland words is also useful, and an early example of such a thing - so from a historical as well as a literary point of view there's a lot of interest going on here. I have various collections of poetry on my shelf, including plenty of Victorian favourites - and very useful they are for providing context for other books and paintings of their time, but nothing quite like Broken Lights, which in the normal way of things would probably have been long forgotten, even if Auld Maunsie's Crü had somehow managed to survive on its own. Yes, I think what we have here is a mixed bag, but it's got a lot of good stuff in it both in the form of the poems, and what it says about the poet and his community and it's a privilege to be able to get our hands on this collection again.

Available from Michael Walmer books, or through The Shetland Times

Tuesday, August 3, 2021

Guilty Creatures - A Menagerie of Mysteries - Edited by Martin Edwards

I've sold the books that I could bear to part with - my sitting room wall looks oddly empty now that the couple of hundred volumes stacked against the radiator have gone, and though it doesn't seem to have made any difference to what space is left on the shelves (an indication of how many books were stacked under things, or just in piles against things) collectively the whole lot seems a little less daunting now. I have a much better idea of what I've got sitting around, can find the books I want more easily, and have slowed down the knitting and increased the amount of reading I'm doing in the last few days. It feels good.

The choice of books has undoubtedly helped on the feel good front too, and after 'English Pastoral' and 'The Eternal Season', 'Guilty Creatures' seemed the obvious choice for something different but nature related. It was also a good choice.

I'm a long term fan of the British Library Crime Classics, particularly it's short stories, and the best thing about that has been seeing how the series continues to evolve. I suppose it could have lost momentum, but as it is both this and the Weird Tales just continue to improve. This is probably partly due to the breadth of topics both now cover. I'd also like to think that there's a shared confidence between the readers and the team behind the books. I'll make the assumption that anything in the series is worth a look, because so far it always has been.

'Guilty Creatures' is blessed with a particularly lush cover, it's from a vintage railway poster celebrating the wildlife of Norfolk. The Heron in particular has an extremely stabby look about it and the bearded tit next to it doesn't look much more friendly, it's an inspired choice.

The stories themselves are great, with the possible exception of the late Conan Doyle (from 1926) that starts the collection. Conan Doyle liked it, and Martin Edwards puts in a good word for it, but the title is a massive clue so I knew the answer far to soon. On the other hand it has a bit of fun with Holmes and that's enjoyable - and starting these collections with a Conan Doyle story is something of a tradition.

The best thing from my point of view though is that a lot of these stories verge on the weird - two passions in one collection is a bonus. F. Tennyson jesse's 'The Green Parakeet' definitely has a weird element, and so I think does H. C. Bailey's 'The Yellow Slugs'. I might put Christinna Brand's 'The Hornet's Nest', and Garnett Radcliffe's 'Pit of Screams' in the same category too - all of them are more mystery than weird, but all have something a little uncanny and gothic in their atmosphere.

It's a splendid collection, the animal theme is perfect for bringing together a particularly diverse range of stories, and that in turn makes it my favourite kind of lazy afternoon reading. Highly recommended.

Monday, August 2, 2021

The Eternal Season - Stephen Rutt

I'm late reading this and unsettled by how quickly this year, and especially this summer, is passing. Walking the dog for my mother this weekend the sloe bushes that seemed to be a mass of frothy blossom only a couple of weeks ago now have berries on them - still green, but probably ripe by the next time I'm likely to be out that way on a couple more weeks. The damson tree by Barrow on Soar train station is covered in ripe fruit, and dropping them onto the platform - although the tree itself is frustratingly out of reach for foraging purposes, and if last year was strange, this one seems stranger still to me.

My copy of 'The Eternal Season' is an uncorrected proof with a short list of selling points printed on the back, including the assertion (which I absolutely agree with) that Rutt is 'Widely acknowledged as one of the brightest young stars writing about the natural world, gathering increasing support and recognition'. I'm tempted to make some sweeping generalisations about nature writing here, but I don't read quite enough of it to be sure of my ground. what I do know is how accessible and inspiring I find Rutt's writing.

One part of the reason for this is that he so often focuses on the local, and obviously, even more so for a book written during Covid and lockdowns, the bigger part is that he writes really well. But the local matters - for all sorts of reasons local is all I, and most of us, have reliable access to, and we all need to think about it a little bit more. I'm lucky in that my part of the city has some good green space that isn't over manicured and is in its way reasonably wildlife-friendly. It could be so much more though, and as books like this make clear, it needs to be.

There are a lot of stark and worrying figures in here about the depletion in numbers of once-common species, as well as the spread of new to us species, some benign, others a threat to our native wildlife. Global warming and global trade are the forces behind this, and I guess the overall message of this book (and James Rebanks English Pastoral) is to think and act globally as well as locally. They were interesting to read together as there's a good bit of overlap in thinking, but for me, The Eternal Season was the more useful book* - it covers more that I didn't know or was only dimly aware of and gave me more to think about.

I hadn't, for example, really considered what the change in seasons means for the food supply of birds who need to time their egg-laying to catch peak grub season, and that they might not be able to keep pace with the insects on that. It's also been easy to think about the damage to habitats here, but forget where they live the rest of the year. That's the oversimplified version, this really is a good place to start learning and thinking more about the everyday effects of climate change.

It is in the end quite a hopeful book too. Things are bad, but there are things we can do now before they get worse if there's a will to do so. This should be, could be, a powerful moment for change too - we've had 18 months in which to really appreciate how much nature can help us on a day to day basis, to realise its value to society, we've learnt that we can adapt, change our behaviour, and give up certain habits if we need to. I don't know how optimistic I am that it'll happen, but at least I'm not totally without hope, and that's very much because of the growing number of books like The Eternal Season. I'm thinking of Stephen Moss' The Accidental Countryside particularly, as well as English Pastoral, and there are others.

The thing they all have in common is a call for a collaborative approach, and asking us to notice what we've got before it's gone. To value what's on our doorsteps as much as we might do the more obviously rare and charismatic species, and to understand something of how big the systems we all live in are.

Beyond all that, this book is also really good company. The balance between being informative and chatty is just right, it doesn't lecture, but it provides endless avenues to follow - some of them truly unexpected. It's also an excellent book about what 2020 was like, good bits, bad bits, strange bits, but the thing that resonated with me most was this paragraph about wildness:

The wild is subjective and hard to define. But it's important for me to be somewhere open, somewhere our physical influence recedes and the lives of other species play a bigger role; to feel as if I am in a place that is shared, not dominated. It is good for us and good for everything else here..."

*I do mean for me, and useful rather than better - this isn't a comparison of their relative merits.